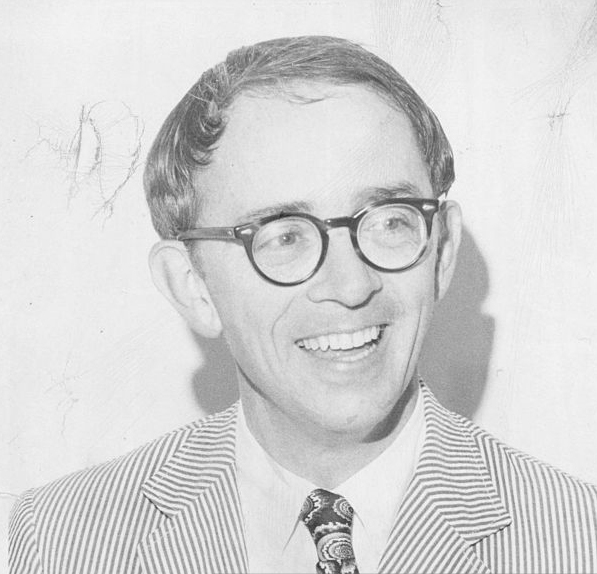

The Barnes Foundation was created in 1922 by Albert Barnes (1872-1951), making his magnificent art collection (rich in work by Matisse, Renoir, Cezanne, Picasso and other masters) available for public viewing and education. He hired the neoclassical architect Paul Philippe Cret (1930 Award) to design the elegant building, which showcased the collection on Barnes’s Main Line estate. An eccentric art enthusiast and chemist who made his fortune by developing the anti-gonorrheal drug Argyrol, Barnes had strong views on how his collection should be viewed, which he stipulated in the indenture of trust setting up the foundation.

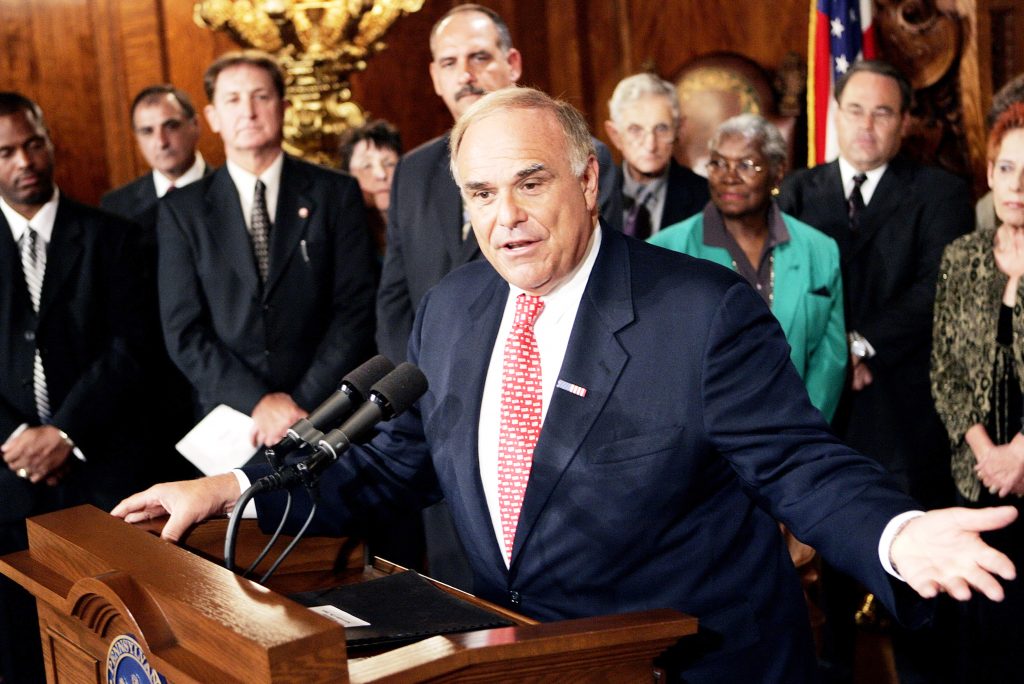

In 2002 the board of the Barnes Foundation decided that, to uphold the foundation’s mission of public accessibility as set out in the trust, they had to challenge the provisions in the indenture requiring the collection to be viewed as it was installed in Merion. Residents had long complained of tour buses in the affluent neighborhood, and the membership and number of visitors to the financially struggling foundation were a fraction of what it could be in the city. The following year, Neubauer and Roberts were appointed to the board, as part of a campaign to revitalize the Barnes.

Neubauer and Roberts stood bravely in the face of virulent opposition from the Friends of the Barnes and other opponents of the proposed move, who contended that the invaluable Barnes experience could only be had by visiting the galleries and arboretum on the 12-acre Lower Merion estate. The issue played itself out in Montgomery County courtrooms, ending on October 5, 2011, when the Friends of the Barnes decided not to appeal the second decision (the first in 2004) of Judge Stanley Ott authorizing the change of venue.

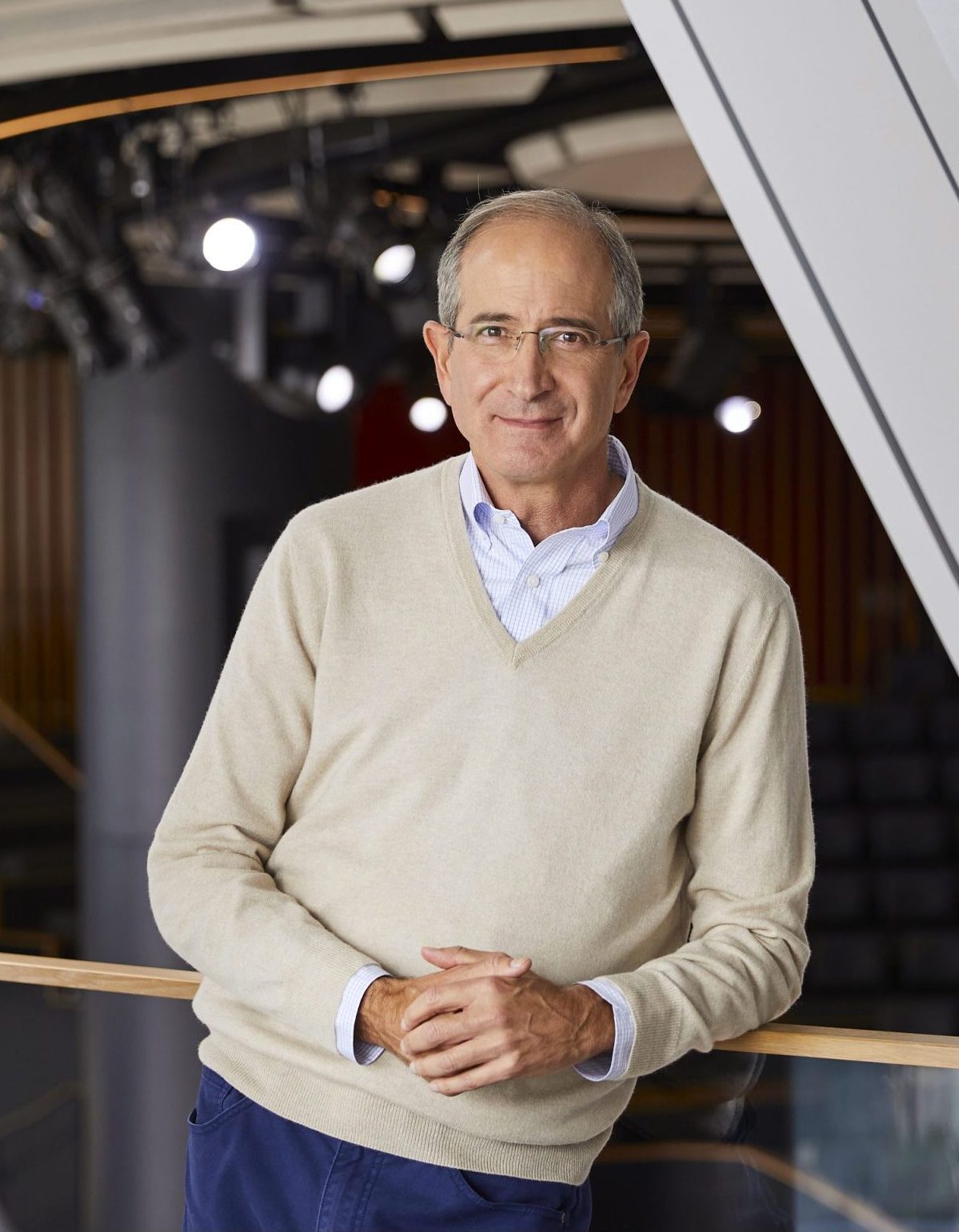

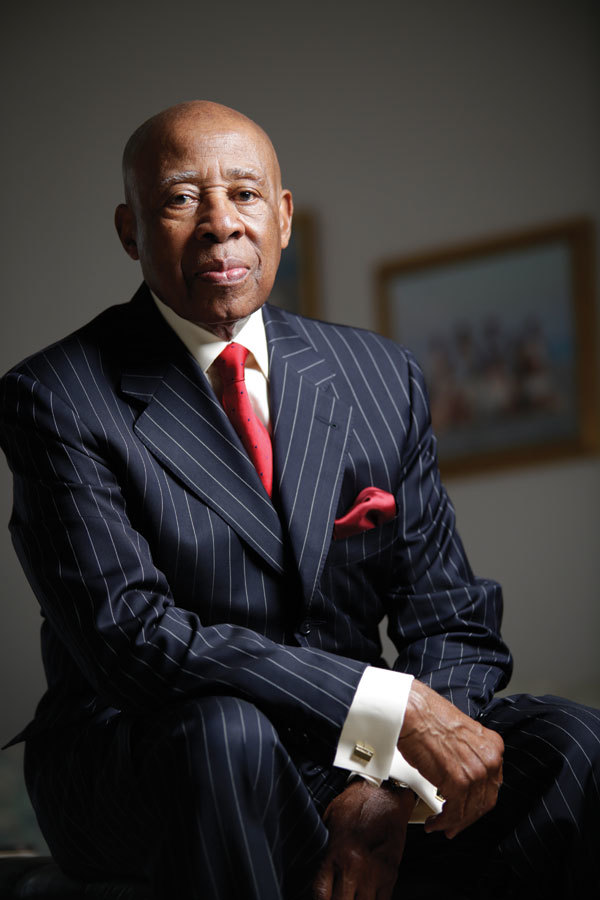

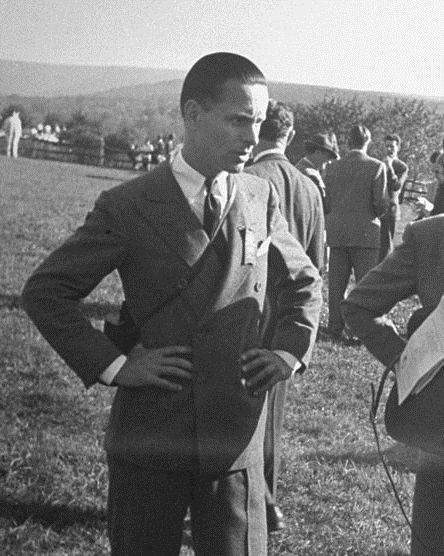

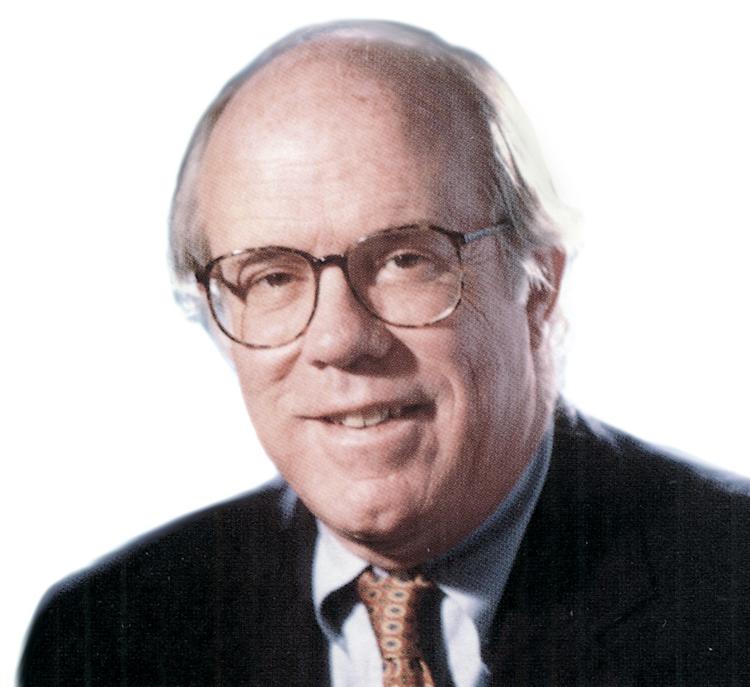

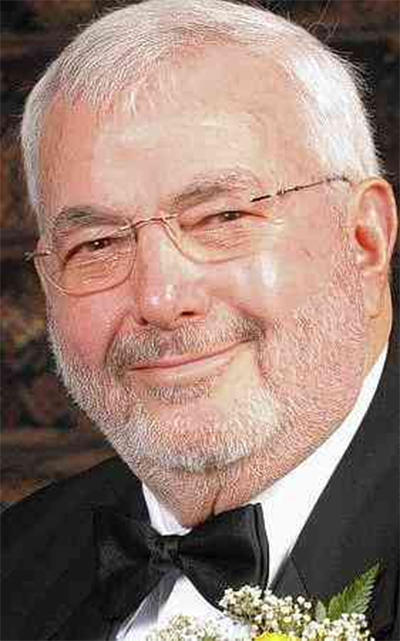

Joseph Neubauer was born in Israel after his parents fled Nazi Germany. At the age of fourteen, he immigrated alone to the United States to further his education while living with his aunt and uncle in Danvers, Massachusetts. He learned English by watching John Wayne movies. Neubauer earned a Masters degree in Business Administration from the University of Chicago. From 1965 until 1979, Neubauer held various executive positions at Chase Manhattan Bank and PepsiCo. Since 1983, Neubauer has been the chief executive officer and board chairman of ARAMARK, a leading provider of facility, uniform, and food services to businesses, sports venues, schools, hospitals, and universities. In 2012 the company had over 250,000 employees in 22 countries. The Neubauer family established the Neubauer Family Foundation, which has funded fellowships in numerous universities and contributed to many cultural institutions, including the Philadelphia Orchestra and WHYY.

As vice chair of the board and head of the development committee of the Barnes Foundation, Neubauer employed his characteristic ebullience to persuade potential donor -- individuals, corporations, and foundations -- of the wisdom behind the proposed move. While readily conceding that the “fantastic collection” would attract some visitors even “if we put it in a Quonset hut,” Neubauer argued that the planned creation of a much more accessible space adhered to Barnes’s original vision. Barnes had been alienated from the stodgy art establishment of early 20th Century Philadelphia, whose conservative tastes did not embrace the work of the impressionists and early modernists. In the spirit of Barnes, the new museum would include ample space for the work of contemporary artists. Barnes had established his foundation to educate “the working classes,” rather than cater to Philadelphia’s social elite. The new museum would have extensive educational programming, which together with its central location, would bring art and art appreciation to an immensely larger number of people. The museum would be a boost to Philadelphia as a tourist location, establishing an art corridor on the Parkway of the Barnes, the Rodin Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

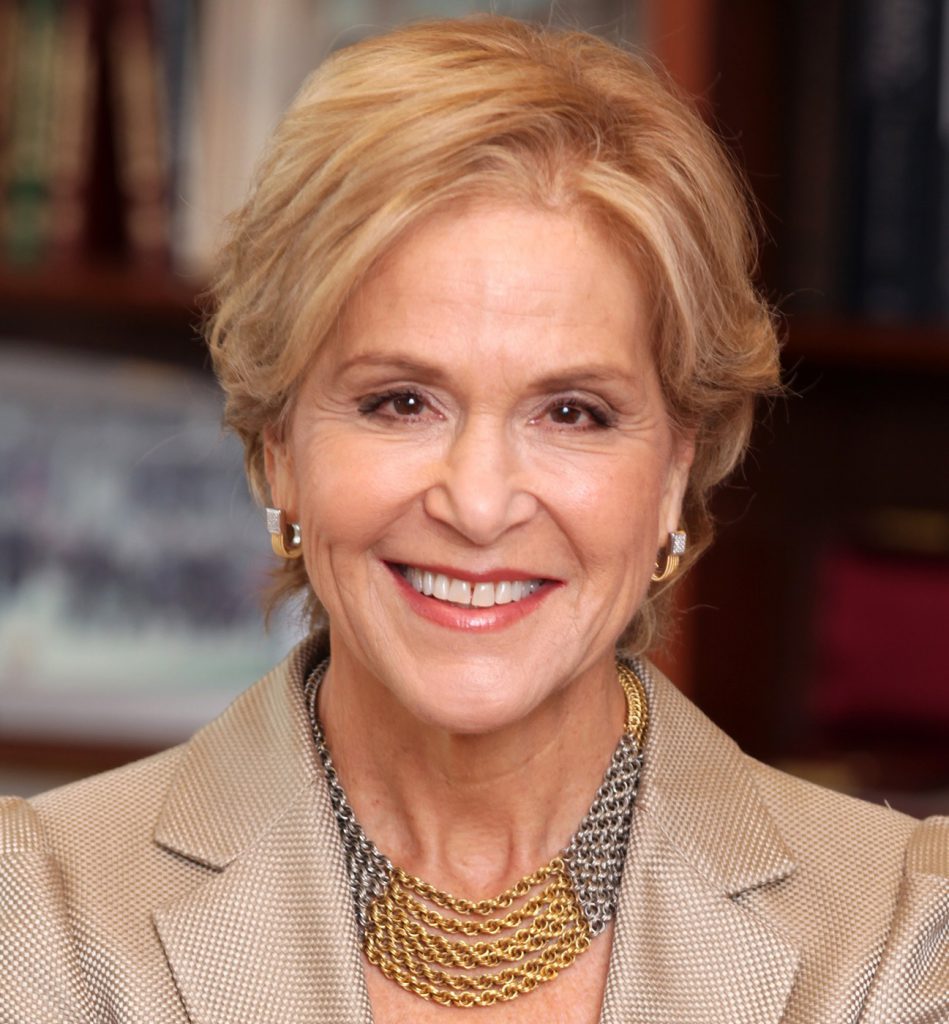

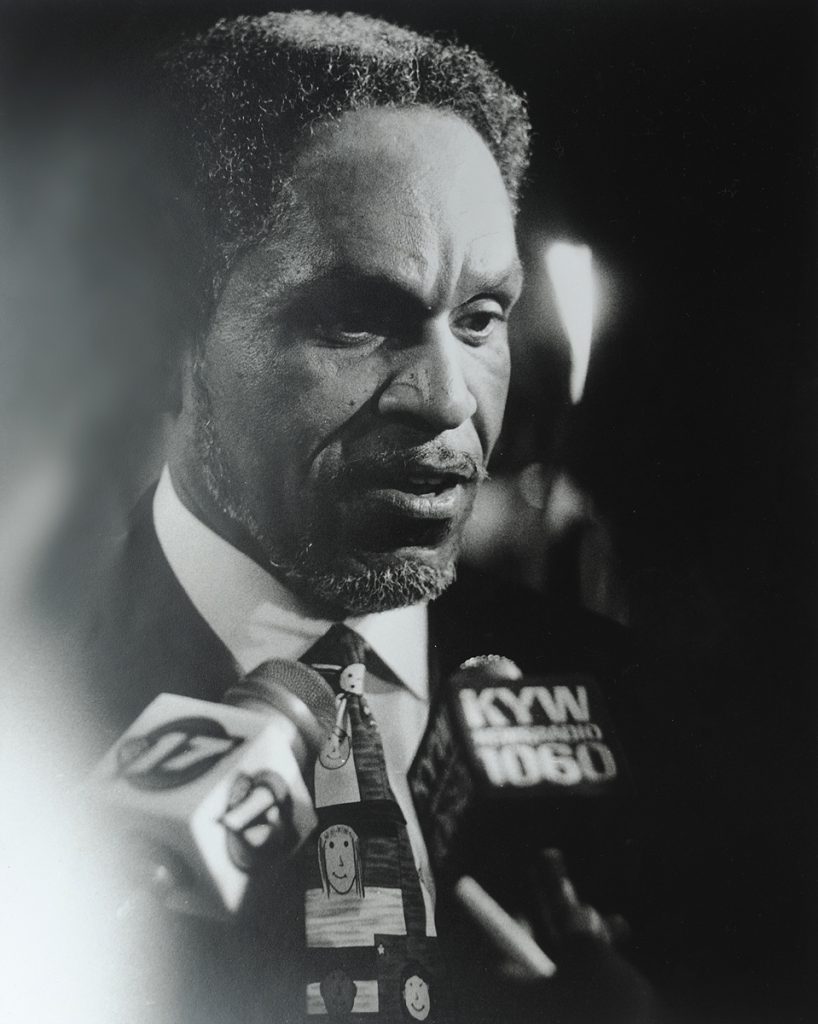

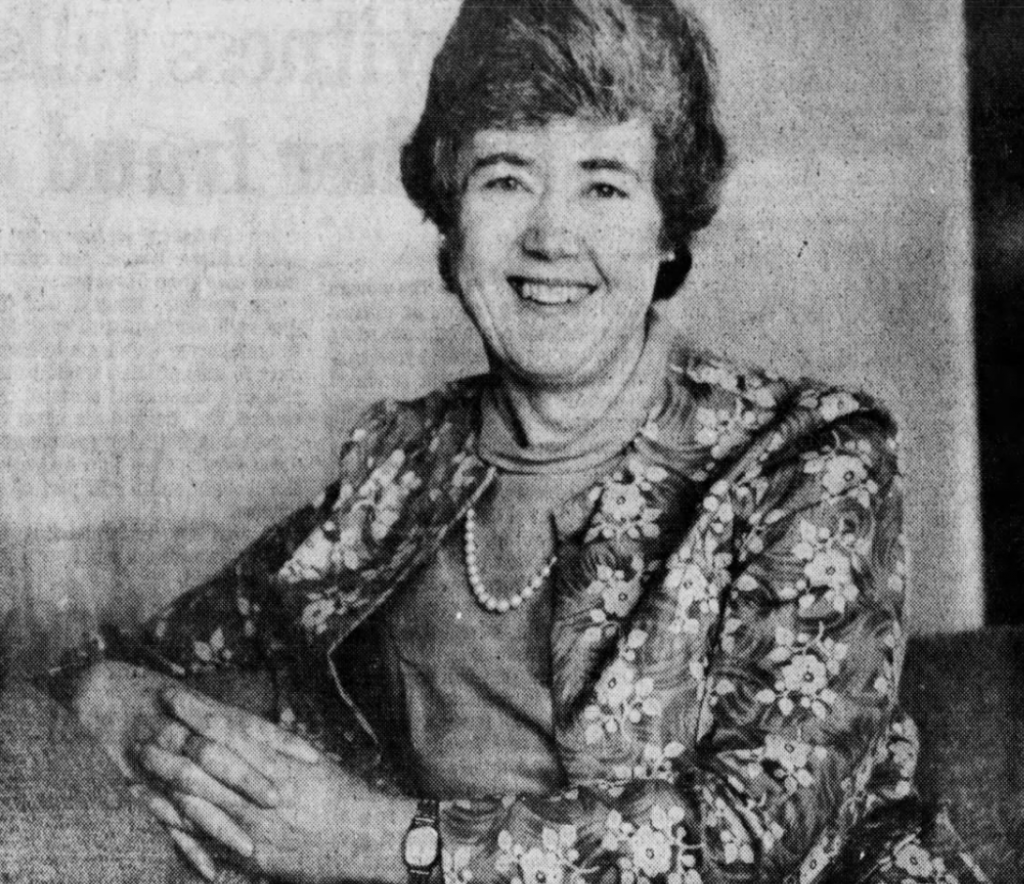

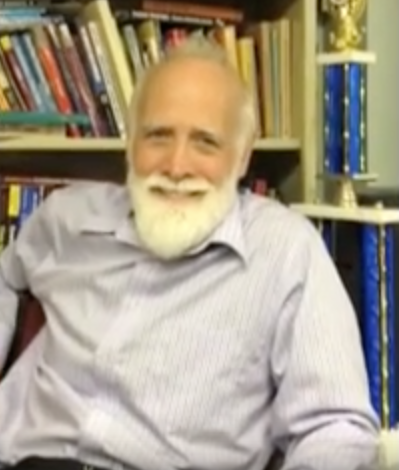

Aileen Roberts, a philanthropist and civic leader, studied architecture and design at North Carolina State University and the University of Pennsylvania. Roberts is the president of the Aileen and Brian Roberts Foundation, and is a leading board member of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She has served on the boards of the Franklin Institute, the Avenue of the Arts, and the International House. Her husband is Brian Roberts, chairman and chief executive officer of Comcast Cablevision, a Fortune 100 company. Roberts has been a planner and volunteer for Project H.O.M.E., an activist group that provides services and lobbies on behalf of the homeless. Roberts and her husband, together with Lynne and Harold Honickman, were honored for funding the group’s $13.5 million learning center in North Philadelphia, providing computer labs and other services to help homeless people turn their lives around.

As chair of the board’s building committee, Roberts oversaw the selection of the architects and architectural plan. In an interview in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Roberts reflected that the project was “enormously complicated,” because of “site constraints, budgetary demands, and the mandate to replicate the Barnes galleries.” Architects and academics were widely consulted by Roberts and her colleagues. To find the right architect and design, Roberts inspected (by her own count) 25 to 30 museums in America and Europe “to see what was the newest, latest, and greatest that we could do.” In 2007 the exhaustive search ended with the selection of architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien.

Completed in early 2012, the museum is a two-story, 93,000-square foot building, with a 12,000-square foot space housing the original Barnes collection, closely replicating the unique, densely hung galleries of the museum in Lower Merion, as stipulated in the trust. The building features a 5,000-square foot Special Exhibitions Gallery, classrooms, auditorium, conservation lab, research department, gift shop, and outdoor café. Roberts described the design features which reflected, and even enhanced, the closeness to nature of the Barnes experience in Lower Merion: “Set in generous gardens with walkways and water features, this dignified building has a unique glass canopy that will filter natural light into the galleries during the day and by night will be a softly glowing beacon.” Moreover, the Barnes estate in Lower Merion would remain open to the public, featuring the foundation’s famed gardens and horticultural program.

An admirer of the sculptor Ellsworth Kelly, Neubauer commissioned the construction of Kelly’s sculpture, The Barnes Totem. The 40-foot stainless-steel totem, outstretched toward the sky, is stationed near the entrance of the museum, facing a pool lined with ten red maples. Neubauer declared that the sculpture was a welcome sign to the visitors and passersby of the museum.