1984

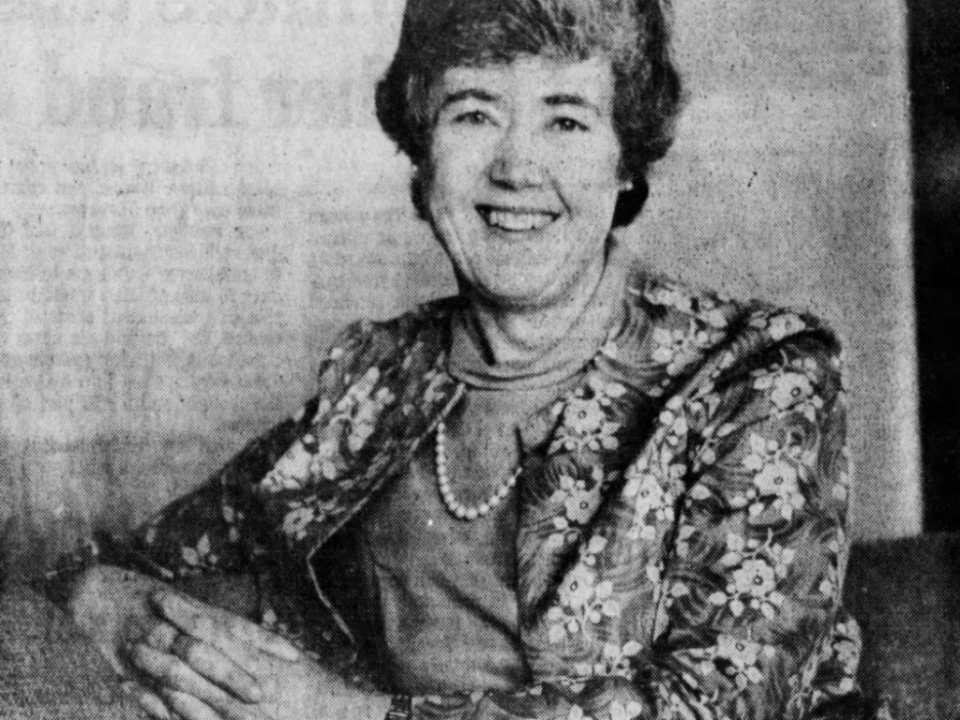

Allcock was leaning toward accepting a position in Nigeria until some friends of hers suggested another plan—purchase a house in a poor section of Philadelphia, and service the needs of the neighborhood. Inspired by the civil rights movement, Allcock took up the challenge, purchasing a house in Germantown. She and her friend, Joan Hemenway, founded what would later be called Covenant House. Hemenway became her lifelong companion.

Allcock noted, “We called it ‘the ministry of being there.’” In fact, no one knew she was a doctor for the first two years. Allcock and her colleagues tutored neighborhood children in reading, established a library for them, and later started a nursery school.

In 1965, Allcock secured her medical license as well as enough money to purchase some medical equipment. She placed her medical sign on the premises, and began accepting patients. She faced resistance at first, as people were not accustomed to a female physician. As Allcock recalled, “nobody believed it. Doctors weren’t women and doctors didn’t roller skate down the street. But the children knew me and trusted me, and they’d bring in their parents, and gradually we built up a medical practice.”

Covenant House thrived, and by 1985 was located in two houses on East Bringhurst Street, with nearby modular clinical units. The clinic had 32 full time staff members, including four physicians. Patients were charged on a sliding scale (based on their ability to pay), and the clinic ran on a break-even basis. In a 1984 article on hunger in Germantown, Allcock testified that a large number of the one thousand babies seen by the clinic each year showed signs of malnutrition.

By 1985 Allcock’s principal activities had changed, from her early days as an active physician to being Covenant House’s executive and medical director. As she noted, “I traded in my stethoscope for a calculator.” Allcock raised funds to support the operating expenses of Covenant House.

Allcock served as the director of Covenant House Health Services for 25 years. She later earned an M.A. in Landscape Design, and relocated to Connecticut. Allcock became an activist in the Guilford Conservation Commission from 2004 to 2010, including serving as its chairperson for five years. Allcock led many conservation initiatives in the town of Guilford, CT, including establishing a research orchard for the purpose of developing “a blight resistant Chestnut Tree.” She also served as a director of the American Chestnut Foundation’s Connecticut chapter. In 2010, Allcock planned on returning to Pennsylvania.

In presenting her the 1984 medal, the Philadelphia Award committee praised Allcock as one who “has set a model for health care practitioners and institutions throughout Philadelphia and beyond.”

1983

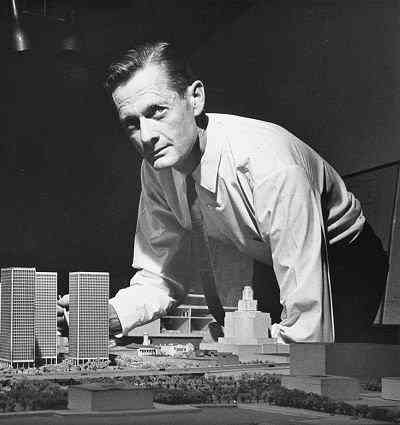

Bacon graduated from Cornell University’s School of Architecture in 1933. With the economy in the grips of the Great Depression, Bacon used a $1,000 inheritance to travel around the world. While in Egypt, Bacon learned that there was a building boom in Shanghai, China. He obtained employment designing public and private projects in Shanghai. After his stint in China, Bacon studied city planning at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. He was a city planner in Flint, Michigan, and then director of the Housing Association of the Delaware Valley, before serving in the Navy during World War II.

In 1946 he began working for the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, a new agency which he had helped create. Bacon was appointed executive director in 1949. Advising four mayors who won and lost elections, Bacon remained a fixture with the planning commission until his retirement in 1970. He remained active as a planning consultant. The Philadelphia Award was presented to him in April 5, 1984 for being “a pioneer in urban revitalization, a person with a creative mind and spirit and one who has earned the gratitude of the people of Philadelphia and its environs.”

The city planning commission did not wield political power, so Bacon used persuasion and savvy to bring his ideas to fruition. His planning involved the center, west and northeast sections of the city, but he is best known for a residential neighborhood, an office development, and a retail commerce site – namely, Society Hill, Penn Center, and The Gallery and Market East, respectively. Under Bacon’s direction a low-income neighborhood with deteriorating colonial and Victorian era housing was transformed into what became known as Society Hill; a massive stone viaduct, a.k.a. the Chinese Wall, was torn down, and replaced with the office buildings of Penn Center; and businesses (via Market Street East and The Gallery) were introduced to the rundown area east of Market Street. He was also instrumental in the creation of Independence Mall.

A nationally influential figure, his vision for the city is captured in his essay, “The City Image,” published in Man and the Modern City (1963). Bacon argued that the city image must be sharp and clear but, above all, consider the human beings populating the area. Creating a humane city is achievable, Bacon believed, if city planning avoids abstraction and focuses on the environment that real people inhabit. He envisioned a city (with the focus on Center City) that would be clean, appealing, and symmetrical, with thriving businesses and offices, historic architecture, and plenty of open spaces. Blueprints for designing post-industrial cities were not available to him, so his hypotheses were based on his “field experiences in city rebuilding.”

Bacon had his critics—community activists decried the gentrification of Society Hill as unjust to the poor; historic preservationists charged that he had historic buildings torn down for his projects; advocates of “mixed use” design criticized his planning for being overly formal. Yet however imperfect, Bacon was a pioneer in the continuing revitalization of Philadelphia from a declining, deteriorating post-industrial city into a renewed, vital, modern metropolis.

1982

Raised in Buffalo, New York, Johnson and her husband Rod, adopted their first child in 1967. Loie was a newborn of Iranian-American descent. The Johnsons fell in love with the baby immediately. After moving to Philadelphia in 1968, the Johnsons struck again by adopting Gregory, a mixed race infant of eight months, and Dennis, a black child of sixteen months. During the 1970s Johnson experienced the trials and joys of raising a multi-racial family. She organized the Open Door Society, a network of bi-racial families that strove both to support the parents and to ensure that their children had ample opportunities to learn of their own cultural heritages.

Johnson soon realized, however, that there was more to be done. She founded the Delaware Valley Adoption Council, with Paddy Noyes, a newspaper columnist and fellow adoptive parent. Their first project was when they proposed what eventually became, “Friday’s Child,” a column in the Philadelphia Inquirer that showcases a child up for adoption in hopes that a wanting family would see him or her and inquire. At first the process was slow. Many adoption agencies were unwilling to put their children in the news media, fearful that advertising children in this way was ethically suspect. Undaunted, Johnson and Noyes pressed forward and convinced two adoption agencies to allow some of their children to be posted in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. The response from prospective adoptive parents was overwhelming, and the column is now a major tool in the adoption process.

Still, Johnson, wanting to do more on behalf of “hard-to-place” children, founded the Delaware Valley Adoption Resource Exchange (DARE) in 1972, a multifaceted agency and umbrella organization that focused on matching children with prospective adoptive parents. In 1975, the Adoption Center of Delaware Valley was formed, with Johnson as its executive director, and DARE as its most important program. The expanded organization was also active in community outreach and policy advocacy. By 1983 the organization had placed over 800 children.

The largest boost to the center came in 1983, when the center received a $350,000 grant for a national website to facilitate their work online, which would be called, “FACES of Adoption: America’s Waiting Children,” (adopt.org). The center essentially was transformed into the National Adoption Center and was officially partnered with the federal Department of Health and Human Services. As a result of Johnson’s efforts, twenty thousand children were adopted.

At her award ceremony, Johnson reminded the crowd that many children “still wait and dream of becoming permanent members of families.” In a 1999 interview, Johnson said: “There are 110,000 kids out there, free to be adopted…We truly believe that there are no unwanted children, just unfound homes.” In 2004 Johnson left a thriving organization behind when she retired as executive director of the National Adoption Center.

1981

Wolf was a gifted student who graduated at the age of fifteen from the William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia. He continued his secondary education with “three years of polishing” at the Bedales School in England. He credited the classical liberal education he received there for his ability to adapt to diverse academic fields in his work.

Upon returning home in 1930, his father Morris Wolf, a leading Philadelphia lawyer, arranged for him to work at the rare-book firm of A.S.W. Rosenbach, one of the world’s premier antiquarian book dealers. “What a wealth…of treasures I handled…scrutinized, marveled at, and sometimes read,” Wolf recalled, “ranging from a twelfth-century manuscript with carved and painted oak covers…to the manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence Benjamin Franklin sent to Frederick of Prussia.” “For over two decades I worked in the shadow of Dr. Rosenbach, the boy in the back room” who wrote and edited the firm’s printed catalogues. His prolific and stylistic contributions to the catalogs and other publications earned him the reputation of a respected scholar in the rare-book world.

In 1952 Wolf left the Rosenbach firm and was hired as a consultant to the Library Company of Philadelphia. His survey unearthed innumerable rare books, pamphlets, and prints, unrecorded in the card catalogue and unknown to the board of directors, including works by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, and the copy of Du Pratz’s History of Louisiana that Merriwether Lewis had carried with him during his expedition. His report to the Board was “unequivocally upbeat” – and in 1953 Wolf was hired as Curator, and in 1955 as Librarian, to implement his own recommendations.

Under Wolf the library was moved from its deteriorating, damp facility at Broad and Christian streets to its current location at Juniper and Locust. The massive library of contemporary fiction and biography, acquired to make the library relevant to the public, was discarded. A new cataloguing system for shelving and recording the library’s holdings was introduced. Wolf’s passion for rare-books compelled many prominent Philadelphia families to donate their private collections. He shrewdly purchased books and manuscripts on subjects not in demand in the rare-book marketplace, including books and manuscripts by or about African-Americans. Wolf further established the library’s reputation through lectures and publications, including, rich in prints and photographs, Philadelphia, Portrait of an American City (1975).

Popular exhibitions at the Library Company, curated in large part by Wolf, included “Bibliothesauri: or, Jewels from the Shelves of the Library Company” (1966), “Negro History, 1553-1903” (1969); and “A Rising People: The Founding of the United States” (1976). The accomplishments of Edwin Wolf II, or as he preferred to call himself, “Dinosaurus Bibliothecarius,” were celebrated in “The Wolf Years” (1984), featuring the acquisitions he secured, his exhibitions, and his writings.

Wolf admired, and successfully modeled himself upon, the great librarians he had known, such as Clarence Brigham at the American Antiquarian Society—“consummate rare-book men, autocratic individualists, who in their way made great libraries greater.”

1980

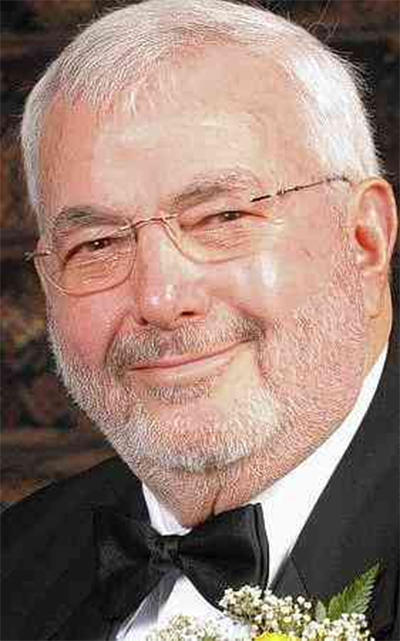

Since then the Foundation has grown to include Dream Village (a 22-acre complex to house families of children who are visiting one of the Orlando theme parks); Dreamlifts (a chartered airplane service to enable children, who cannot stay away from medical care or home for more than 24 hours, to have a daytrip to one of the Florida theme parks); and Progeria Reunions. Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is an insidious rare genetic condition which causes physical changes that resemble accelerated aging in children. The Reunions are week-long getaways for fun and friendship. The foundation has come a long way from when Sample had to take out personal loans to fund the projects. In 1983 Sample retired from the police force to devote himself full-time to his work as president of the foundation.

Like all things that grow, the Sunshine Foundation has had growing pains. In 1987 the foundation came under investigation by the attorney general’s office for mismanagement. No charges were filed. Sample’s defenders asserted that he was a former cop with a big heart, not an accountant. Sample rode out the rocky times, still serving as president. Sample did step down in 2009 and now has the title of President Emeritus. His wife, Kate, serves as president of the foundation.

His legacy speaks for itself. The Sunshine Foundation (now based in Feasterville) has granted the wishes of over 34,500 children, funneling 85% of all donations directly to children’s programs. The American Institute for Philanthropy now lists it as a top-rated charity. Aside from the Philadelphia Award, Sample has received many other awards, including President Ronald Reagan’s Volunteer Action Award and the Please Touch Museum’s Great Friends to Kids Award. Villanova University granted him an honorary doctorate.

1979

Pneumococcal pneumonia was a major killer of the elderly and chronically ill. At the time of his research, over 90 strains of pneumococci had been discovered. What Austrian did was identify those types that most frequently caused disease. His 1977 vaccine contained antigens of 14 serotypes (serotypes are distinct variations of a bacteria or virus). In 1983 he introduced an improved version of the vaccine, containing 23 serotypes, which accounted for 85% of the infections associated with pneumococcal pneumonia. All his research developing the vaccine took place at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was on the faculty since 1962. Ever seeing the need to perfect the vaccine, up to the week he died, Austrian was testing strains of pneumococci sent to him from doctors around the world.

Austrian was no stranger to infectious diseases. His father, Charles Robert Austrian, studied infectious diseases as a professor and internist at John Hopkins University. After graduating from Johns Hopkins Medical School, Austrian studied pneumococcal infections under Dr. Barry Wood. During World War II Austrian served in Fiji, treating casualties. It was at this time that he also worked on research to treat malaria. He then went to Burma to study typhus.

After the war Austrian challenged the prevailing medical wisdom that, with the introduction of penicillin and other antibiotics, pneumococcal infections had become a minimal danger to patients. While an internist and scientist at Kings County Hospital and the State University of New York in Brooklyn, Austrian, with Jerome Gold, demonstrated that pneumococcal infections often went undiscovered by standard testing, remained commonplace, and often resulted in mortality. Austrian’s contribution in fighting pneumococcal infections was thus two-fold—first proving the need for a vaccine, and then developing a vaccine that saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Always the professional, Dr. Austrian was known to never being seen without a jacket and tie. Professor Stanley A. Plotkin wrote of Austrian: “If there is one word that summed up the man and the physician…it was elegant: elegant in person, elegant in thought, and elegant in action.”

1978

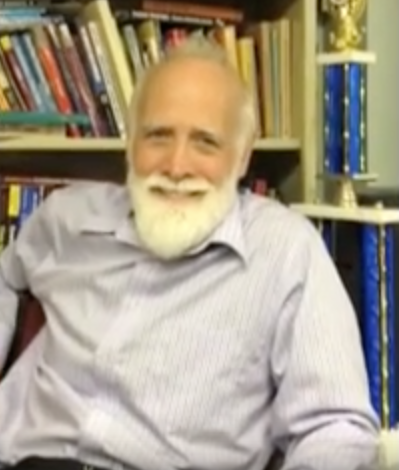

But like most devoted teachers, these men spent a good deal of their personal free time (and disposable income) coaching the teams, sponsoring trips, and mentoring the students. Chess does so much for a young person, by promoting patience, planning, and analytical thinking. These skills are especially valuable for young persons faced with seemingly limited choices and options. Moreover, studies have shown that students who play chess develop significantly higher math and reading scores (and better grades) than control groups that do not play chess. And winning builds confidence.

At the time the award was made, the chess team at Vaux Junior High, under Sherman, was preparing to go to Yugoslavia for a rematch (hoping to tie up their 0-1 loss to students from Belgrade, whom they had played via satellite). With no financial support from the Philadelphia School District, while in Belgrade the students stayed at the homes of host families. Although losing to the Yugoslavians, the Vaux team had won four city championships, three state championships, and two national championships. Shutt’s chess players were no slouches either. Founded in 1971, his team had placed nationally and many of its team members had gone on to join the Vaux team. Shutt had his young players practicing two hours a day.

By 1983 the Vaux team, dubbed in 1977 as the Bad Bishops (the Douglass team was a tamer Mighty Pawns—the inspiration for a 1987 PBS Wonderworks telemovie of the same name) and by then under another coach (Sherman left in 1979), had racked up eight national championships (seven consecutive, 1977-1983). By 1987 the Mighty Pawns had won twelve straight elementary school titles. Shutt said of competitive chess: “Turn kids on to chess, and you’ll see they love the strategizing, the scheming. Take a high-energy kid and give him a competitive thing, and he’ll stay rooted to the spot.” Shutt, who became a faculty member in the Mentally Gifted Program at the Julia Masterman School, set up a chess team at Masterman, which has traveled to tournaments in Israel and Iceland. He is a leading advocate of the advantages of competitive chess for students.

The Award Committee gave the prize to the two teachers “for demonstrating to us the nobility of teaching when we often are lost in the troubles that beset its institutions; for removing the blinders from youth so they can see the possible horizons; and for helping the rest of us to understand that all our youth have potential and deserve our encouragement and support in exercising their brain power.”

1977

This was both a new, yet logical role for Rauch, given his past experience in civic engagement. Until that time Rauch was more likely known as the head of Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS), which he presided over as president or chairman for twenty-five years until his retirement in 1979. He was also a respected figure in the business community, who had played a vital role in the revitalization of Society Hill, the development of Penn’s Landing, and the establishment of the historic district. He was contacted by civil rights activist Cecil B. Moore, who told him that the business community had to act quickly to avert riots.

Calling itself the Good Friday Group, the group that formed was an uneasy coalition of white business leaders, black moderates, and black militants which first met in the board room of PSFS. Rauch committed $1 million from businesses to spend on projects developed by the black community focusing on job creation and social services. A determined Rauch then raised the money quickly. William Eagleson, a friend of Rauch’s and fellow banker, stated about this time: “Stew brought to the table a personal presence and integrity that engendered trust among the highly diverse people who had gathered with feelings of suspicion, anger, and even hate. It was Philadelphia’s great good fortune that he was in the right place at the right time.”

Under Rauch’s leadership, the Good Friday Group took on another morsel—literally. The Tastykake Company in the 1960s only hired African-Americans for menial positions. The Rev. Leon Sullivan (the 1965 Philadelphia Award winner and a member of the Good Friday Group), organized a boycott of that company. There were members of the business community who wanted to remove Sullivan from the Group because of this activity. Rauch not only blocked the removal effort, he also sponsored a Group vote to provide financial assistance to Sullivan for the boycott. The pro-Sullivan forces prevailed.

Rauch received the 1977 Philadelphia Award for his leadership of the business community. Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, who had chaired the meetings of the Good Friday Group, saluted Rauch for his longstanding concern and efforts to address the “unmet human needs” of the city. When presenting the award to Rauch, Higginbotham declared, “When you check the major agenda for the physical and human improvements [in the city] during the last 25 years, most often Stewart Rauch has been a key catalyst.”

Economic disparity, racial unrest: what other battles would Rauch have to tackle? The last one involved, perhaps oddly enough, his daughter Sheila. In 1979 Sheila Rauch had a much publicized marriage to the son of Robert F. Kennedy, Joseph P. Kennedy III. Yet after 12 years the marriage ended. But it didn’t just end; Joseph Kennedy sought an annulment from the Catholic Church, stating (basically) that the marriage never occurred. Kennedy succeeded in his endeavor, but not without the objections of Sheila who took her ecclesiastical appeal public and wrote a book about it: Shattered Faith. This must have been such a difficult time for Stewart Rauch and his wife Frances, who had, by all accounts, a loving 60-year marriage. As in many cases of a long, happy life together, Stewart passed away just two weeks after Frances.

1976

Rhoads worked for organizations that were founded by Benjamin Franklin. He was the president of the American Philosophical Society (1976-1984) and chair of the department of surgery (1959-1972) at the University of Pennsylvania, where he had been a surgeon at the university hospital since 1932. Rhoads was provost of the university (1956-1959). At various times, he served as president or chairman of virtually all of the professional organizations for surgeons. The frequency with which he was chosen for leadership positions reflected his reputation for getting things done. Rhoads credited his practice of Quaker consensus building with his success as a leader. He described his technique: “…there are two times when you can speak most effectively in a group. One is when the thing starts off, and sometimes if you then take a strong position, it doesn’t solve the controversy but it sort of directs it. The other way is to wait until the discussion is pretty well advanced and see whether you can find a solution that will reconcile enough points of view to prevail.”

It was his work in the medical field, and primary care surgery, for which he is most remembered. He was a leader of the American Cancer Society, and for twenty years was editor of its journal, Cancer. Appointed by President Richard Nixon, Rhoads chaired the National Cancer Advisory Board from 1972 until 1979. As a professor in the Medical School, Rhoads was renowned as a trainer of surgeons—eleven of his students became chairs of surgery at other medical schools.

As a researcher, Rhoads published over 400 scientific articles in his career. His research focused on problems of nutrition among hospital patients. He began experimentation on this subject during the 1930s, worked on it for decades with colleagues, leading to the invention in 1966, with Dr. Stanley Dudrick, of the practice of intravenous hyperalimentation. This technique involved the puncture of the subclavian vein and enabled feeding of patients who could not tolerate standard intravenous feeding. This major medical breakthrough saved the lives of thousands of patients who were unable to eat.

His work ethic was astounding. He technically never retired. Well into his nineties Rhoads was attending meetings, giving lectures, and writing. Two weeks before his death he was in his office tending to business. His biographers Donna Muldoon and John Rombeau give an example of his fortitude: on a particular day in 1996 Rhoads attended a 7:00 a.m. medical conference at Penn; later that morning he was in Center City attending another meeting; by noon he was at the American Philosophical Society; at 4:00 he was back at Penn for another lecture and dinner. The next day he flew off to Rome for a joint meeting of the APS and the Academia Nazionale dei Lincei. Later he attended a reception at the American Embassy and had an audience with the Pope. The next day he and his wife flew to Sicily to go sightseeing. This was when he was 89.