1975

During his tenure Crawford increased the number of Philadelphia’s recreational areas from 94 to 815, including 84 pools, 47 recreation centers, and nearly 400 parks and playgrounds.

When he retired in 1981, Mayor Bill Green said “I will tell you now who will take his place. Nobody, because nobody can.”

A recognized leader in his field, he served as president of the National Recreation and Park Association and co-founder and executive director of the National Recreation Foundation—the latter now awards an annual Robert W. Crawford Achievement Prize to individuals who make an extraordinary contribution to recreational activities for at-risk youth.

1975

He went on to found the Dental First Corporation, which is now run by his daughter, Dr. Renee Fennell Dempsey. Besides his work in dentistry, Fennell was a social activist. He founded Interested Negroes Incorporated, an organization of volunteers providing career counseling to junior high students. From 1967 until 1982 this organization served over 1500 children per year.

In his later life, he has had to deal with the effects of Lupus. In his autobiography, Reflections of a Closet Christian: A Basic Primer for Life, he writes: “I am a separate and unique individual like no other that God has created.

I feel that I am the culmination of the genes of all my fore-parents arranged in a specific pattern. Every person born can make claim to the same thing, so I’m not so special.” But what Dr. Fennell did with his life was indeed special.

1975

This former gang member, turned gang-patrol cop, turned gang-ministering crusader, acquired a reputation for fearlessness when confronting gang members and drug dealers. After a life as a troubled youth, Floyd reformed his ways, eventually joining the Philadelphia police force, specializing in juvenile aid, community relations, narcotics, gang control, human relations and the morals squad.

A thirteen-year police veteran, Floyd left the force to found the Agape Christian Chapel in Germantown in 1972. Most Philadelphians did not know the church, but they knew its van, outfitted with a stuffed torso sitting up in a coffin with the message: “Take Dope and End up a Dummy.”

Floyd is a relentless crusader (again literally—he founded Neighborhood Crusades, Inc.) against drug dealing, absentee fathers, street crime, and, of course, gangs. He has produced and directed films and commercials depicting the horrors of drug addiction and gang violence.

Floyd has received numerous awards, including Philadelphia Outstanding Policeman (1968), Philadelphia Tribune Humanitarian Award (1971), and Prince Hall Grand Lodge Free and Accepted Masons’ Man of the Year (1977).

1975

Haas steered the Balch Institute to provide educational programs which would promote better intergroup understanding, particularly in Philadelphia. He was an active supporter of the United Way of America and chair of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Philadelphia.

In 2006 Haas and his wife established the Stoneleigh Foundation to serve the needs of vulnerable and underserved children and youth. Besides supporting the Balch and HSP, Haas was instrumental in establishing the Chemical Heritage Foundation (a research center for the history of chemistry) in 1982.

Haas and his wife both received the 2009 Founder’s Award from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

1975

Adecade later, Hayre returned and was hired as the city’s second African-American junior high school teacher. Hayre went on to be the city’s first African-American high school teacher, first African-American principal, first female African-American district superintendent, and first female president of the board of education

She received her bachelor, master and doctorate degrees, all from the University of Pennsylvania. As a principal Hayre established WINGS (Work Inspired Now Gains Strength), a program which encouraged students to discover their talents through college preparatory classes and diverse cultural experiences. After retiring from the school district she turned to philanthropy.

Inspired by millionaire Eugene Lang’s venture providing college education for at-risk youth, Hayre started and personally financed the Tell Them We Are Rising Fund at Temple University. This fund “adopted” 119 middle school students from North Philadelphia and guaranteed their post-secondary school tuition if they graduated from high school.

Nearly half of this cohort went on to two or four-year colleges or technical school. Hayre, wrote, together with Alexis Moore, her autobiography, Tell Them We Are Rising: A Memoir of Faith in Education (1997).

1975

The league primarily supported desegregation, for both students and teachers, in the Philadelphia public school system, as well as another famous, albeit private, Philadelphia educational institution—Girard College. Logan and his organization were instrumental in helping fellow Philadelphia Award winner Ruth Hayre obtain a secondary school teaching position in the district.

Hayre had passed the written exam but when she went before a panel of all-white school principals for the oral exam, she failed. Hayre and Logan challenged their decision and received permission for a retest with a racially mixed group of educators, which she passed.

1975

Under Schoenbach’s leadership, the school focused more on charting and evaluating individual student development and improving performance and instruction opportunities.

The number of students increased from nearly 700 to about 3,000. “When Sol arrived, Settlement Music School was…somewhat exclusive,” explained Robert Capanna, who became executive director after Schoenbach, “Sol walked in and said…why not open the doors?”

Schoenbach was a colorful man known for wearing bright vests and claiming to have coined the name Queen Village for the area in South Philadelphia around the music school. While at the Philadelphia Orchestra, he organized its pension fund, revived its children’s concert series, and formed a credit union for the musicians.

1975

Skid Row is perhaps every large city’s greatest shame, since it brings attention to the city’s failure to provide its most vulnerable citizens solace. But that did not hinder Shandler, even though as the years passed his clientele profile slipped deeper into the depths.

Alcoholism was replaced by heroin addiction, and then “polydrugs”—crack cocaine and alcohol. The addicts became younger, angrier, more aggressive, and much more numerous.

The center, once located at 304 Arch Street, expanded to include three facilities, providing comprehensive rehabilitation and treatment programs for substance abuse. Many of his clients were successful at kicking the habit and turning their lives around; sixty percent of his clients, for example, completed the program at the Washington House facility in 1991. One assumes that those persons who overcame their addition would not consider that small in any sense.

1974

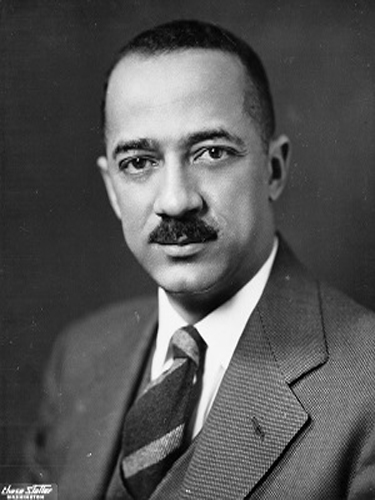

After graduating with a degree in mathematics from Amherst College in 1925 (Phi Beta Kappa and magna cum laude), Hastie taught at the Bordentown Manual School in Bordentown, New Jersey before going on to Harvard University to receive a law degree in 1930. At the time of his graduation, less than one percent of all U.S. lawyers were African American. Hastie moved to Washington DC and joined the black law firm of Houston and Houston (later Houston, Houston, and Hastie). He returned to Harvard, receiving a doctorate of juridical science in 1933.

Hastie was a champion for civil rights during a period when segregation and racial discrimination often went unchallenged. During the early 1930s he argued his first civil rights case, when he represented Thomas Hocutt, an African American who unsuccessfully challenged the whites only policy of the University of North Carolina. Hastie began his federal career as a solicitor for the Department of the Interior in 1933. While at Interior, he penned the Organic Act of 1936, which facilitated the U.S. Virgin Islands transition from Danish colonial law and granted the predominantly black islanders basic American rights, including ending income and property requirements for voting, and extending suffrage to women.

Upon the recommendation of Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, Roosevelt nominated Hastie to the U.S. District Court in the Virgin Islands. After a contentious Senate confirmation hearing, where Southern senators argued that appointment of a black judge would be unacceptable to the people of the Virgin Islands, he was confirmed in 1937. He served at that post until 1939 when he left to become dean of Howard University’s law school.

Roosevelt tapped Hastie again in 1940, for a position at the War Department. He served there till 1943 when he resigned due to the armed forces lack of a commitment to integration. Hastie then wrote several articles condemning segregation in the military. Harold Ickes again recommended Hastie in 1946, this time as governor of the Virgin Islands. After what Hastie described as a “rather vigorous fight,” he was confirmed by the Senate. He served in that capacity until President Truman nominated him for the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals in 1949 (covering Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and the Virgin Islands), eventually becoming chief judge. He sat on the bench to June 2, 1971, retiring to Philadelphia--but continuing to serve as a senior judge. He served as a trustee of Temple University.

William Hastie maintained a long standing relationship with the NAACP, as legal counsel in its battles to ensure salary parity between black and white teachers and to end racial segregation in public education and public transportation. Hastie was one of the architects of the legal arguments that culminated in the landmark Brown versus Board of Education decision. President Lyndon Baines Johnson seriously considered Hastie for the supreme court, but decided instead on Thurgood Marshall, who Hastie had mentored when Marshall was a law student at Howard University; the two men had also worked together on civil rights cases. Hastie received the Philadelphia Award of 1974 for his contributions to civil rights.

Lee Arnold

Sources: Obituary, Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1976; Mario A. Charles, “William Henry Hastie (1904-1976),” Notable Black American Men (Detroit, 1999); Peter Wallenstein, “William Henry Hastie,” African American National Biography (Oxford, 2008); Who was Who in America, vol. 7 (Chicago, 1981); Denise Dennis, “William H. Hastie,” Century of Greatness: The Urban League of Philadelphia (Phila., 2002); John Dubois, “Judge Hastie Receives Phila. Award,” Evening Bulletin, Apr. 8, 1975; “Retired Judge Wins the Phila. Award,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 1975; Francis M. Lordan, “Hastie Wins Phila. Award,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 26, 1975. The following are collected in Philadelphia Award Records, Series 2 (Recipients & Nominees, 1965-1999), Box 7, folder 15: program, clippings; Series 3 (Award Ceremonies, 1922-2004), Box 17, folder 11: clipping. Photo: Image courtesy Enid M. Baa Public Library & Archives, Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Comment: During the 1970s Hastie was critical of black separatism, which he argued would “only lead to greater bitterness and frustration and to an even more inferior status than black Americans now experience.” For him the goal was always full integration into American society, while retaining one’s values in the process.