1973

In 1934 Patrick graduated with a PhD in botany from the University of Virginia. The year before Patrick had enlisted as a volunteer at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, having moved there with her husband Charles Hodge, an entomologist. Her first task was to “clean about 25,000 slides,” but a few years later she was appointed curator of microscopy. Originally told that women scientists were not paid at the academy, Patrick worked for a decade there before receiving a salary. In 1947 Patrick founded the limnology (fresh water biology) department at the academy, and served as its director for over four decades.

Patrick’s research on diatoms, single-celled algae, pioneered the methodology by which water pollution is classified and quantified, based on the types and numbers of diatoms in a water system. Her invention, the diatometer, accurately measures these organisms. Her work with diatoms helped the Allies locate a den of German submarines in the West Indies during World War Two. As Patrick tells the story, “The Navy had captured a German submarine and scraped a bunch of goop off the hull…[By analyzing] the diatoms in it, we were able to determine the location of the hideaway.”

Another landmark effort was her 1948 study of the ConestogaCreekBasin, the first comprehensive survey of the effects of pollution on the plants, animals, and microorganisms in a creek or river. Her approach, encompassing all organisms within a water system, was groundbreaking. Subsequently Patrick led innumerable expeditions throughout the world. She was known for her hip boots and white pith helmet, trusted friends as she waded into more than 850 stretches of river in pursuit of her studies.

Her teaching career at the University of Pennsylvania, spanning more than 35 years, was so influential that a Harvard entomologist called her the “den mother of ecology.” Patrick emphasized hands-on experience and had her students wading in the water on Saturday expeditions. Patrick was a prolific scholar, writing several books and over 130 journal articles. She received more than thirty awards for her scientific work.

Patrick counseled Presidents Lyndon Baines Johnson and Ronald Reagan on environmental issues, and worked closely with both government and industry, serving on innumerable boards and advisory councils. Patrick pursued a practical environmentalism, searching for synergy between industry and environmentalists. In her view, “You can’t have society without industry… But on the other hand, industry has to realize that it is a responsible group.” She was the first female and the first environmentalist on the board of the chemical giant DuPont. Her involvement with private industry occasionally led her colleagues to criticize her for being too conciliatory to business interests.

Fifty years into her career, Patrick scoffed at the idea of retiring. “Retire? Cut back? You must be joking.” At age 99, Patrick was still reporting on a daily basis to her office at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

1972

During this 10-week long program, Eckert and Mauchly began sharing their ideas about computers and the need for a high-speed computing machine. These brainstorming sessions continued “in classrooms, in labs, and over coffee and sundaes at the old Linton’s restaurant on Market Street.” Together they began working on a computer system designed for general numerical calculations. In 1942 Mauchly drafted a memo that outlined their ideas, and the following year he wrote a formal proposal which was greeted with interest by the Army, due to the computational advantages it might bring, especially in the area of ballistics. A classified military contract was agreed upon, the venture was named Project PX, and, with the army’s grant of approximately $500,000, the development of the ENIAC computer was officially underway on April 9, 1943.

The ENIAC, an acronym for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, was completed in 1945 after two and a half-years of development, with the assistance of a staff of two hundred. Officially unveiled on February 14, 1946, the ENIAC contained 18,000 vacuum tubes and weighed in at a remarkable 30 tons, covering the entire 15,000 square-foot basement of the Moore School. Controlled by electronic impulses and hundreds of cables, the ENIAC resembled “an old-time telephone switchboard” on a colossal scale. The speed and accuracy of the computer were unmatched, and, most importantly, it was reliable. Mauchly was the brainchild of the ENIAC’s structural design, while Eckert made the theoretical ideas a functioning reality. A brilliant scientist and a brilliant engineer had the creativity and skills which together created the ENIAC.

The “engineering tour de force” that Eckert and Mauchly created revolutionized technology, science, and business, paving the way for the “Information Age” and modern-day computers. Many consider the ENIAC to be the most significant invention of the 20th Century. In the words of Dr. Marvin Wachman, chairman of the Philadelphia Award Board of Trustees when the award was given, “many of the daily endeavors we take for granted today would be unthinkable without computer technology.” He concluded: “It is especially fitting that the Philadelphia community, in which [their] work began, now recognizes their monumental achievement, which in countless ways, affects the lives of virtually everyone on this planet.”

After the development of the ENIAC, Eckert and Mauchly resigned from their positions at the Moore School due to a bitter dispute with the University of Pennsylvania over the patent for the ENIAC; the university believed the profits from the invention belonged to the institution, not to Eckert and Mauchly. They subsequently formed a business in Philadelphia, originally known as the Electronic Controls Company, where they aimed to manufacture computers for sale. Although the company went through a series of mergers and name changes, they became, through their work for this company, co-inventors of the UNIVAC and BINAC, the first commercial computers. Yet their company struggled to compete with better-financed rival companies, which produced commercial computers including the ILLIAC, the Whirlwind, and the MANIAC.

After the purchase of the business by the Rand Corporation in 1950, Mauchly found himself marginalized within the company, due to the secret nature of the company’s military research and their reliance on their own team of researchers. In a plaintive letter to the company that he never sent, Mauchly wrote, “I am unhappy because my usefulness…has become severely circumscribed. An assured income is all very well, but…I have an urge to do things.” In 1959 Mauchly left and formed his own consulting firm, Mauchly Associates, which advised clients on project planning and the uses of computers. Eckert , who remained as a vice president of the company, obtained 87 patents for his various inventions in the course of his lifetime. But it was their role as creators of the ENIAC, the predecessor of all computers, that changed technology forever and made them true visionaries in the eyes of Philadelphia.

1971

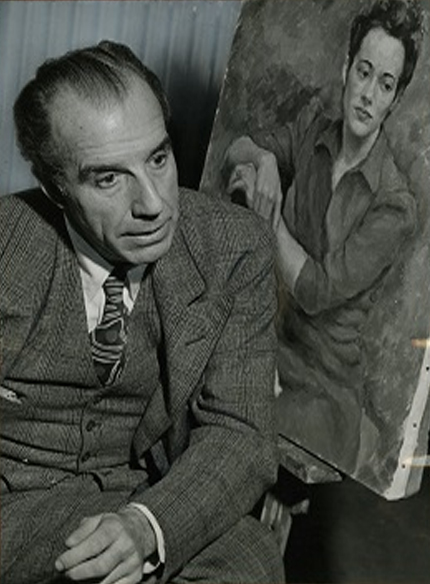

Yet his path as an artist had a couple of detours. He won a Cresson Travelling Scholarship to study art in 1917, but it was withheld due to the War. After serving time in the Navy, he moved to New York City and started off as a commercial artist before winning a second Cresson Scholarship, after which he traveled and studied in France, Spain, Italy, North Africa, Russia and Greece. He won first prize in 1931 at the Carnegie International Exhibition; in 1939 he was awarded a gold medal from the Corcoran Gallery of Art. He taught at the Tyler School of Art (Temple University) from 1940 to 1943. In 1947 Watkins was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He would return to PAFA, this time as an instructor, from 1943 to 1968. In 1958, he was selected as a member of the Cultural Exchange Mission in the Fine Arts to the USSR. His connection with PAFA continued with his serving on their board of directors until his death.

In the art world, he was often, creatively, compared with Cezanne. But, unlike Cezanne, he rejected any identification with expressionism (or other movements). When pressed, he would say that his work was “expressive.” One critic categorized it as: “His canvases are neither direct visual transferences from nature nor arcane cryptograms. They are synergetic.

The power they exude is abrasively generated by the colliding outer and inner worlds he couples through paint.” Even though he was often identified as a portrait painter, he did not regard himself as one. “His attitudes toward a still life, landscape, or figure composition do not differ from his approach to a sitter…He thinks pigmentally…when he talks, he gives the impression that he is squeezing words out of a tube. His palette is his dictionary…His paintings are of paint in the elemental sense that an adobe house is of the earth.”

He was given the Philadelphia Award for not only his painting, but “more importantly for his contribution to art through a quarter century of teaching at [PAFA]…Franklin Watkins’ influence on his art students constitutes one of the major influences of this great artist on the Philadelphia community. This itself is a highly creative gift.”

1970

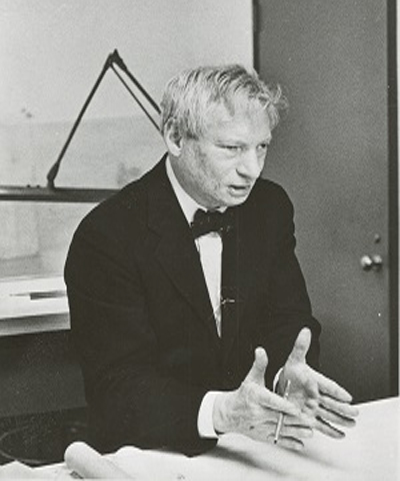

His first major project was as chief of design of the Sesquicentennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1925. Kahn then worked in the offices of several architects, including his professor at Penn, Paul Philippe Cret. In 1935 Kahn established his own private practice, but work was not frequent. Kahn was a practitioner of the International Style, a modernist, minimalist approach to architecture, centered on functionality and rejecting the merely decorative.

Kahn began his teaching career at Yale University in 1948, leaving in 1957 to teach at the University of Pennsylvania where he remained until his death. The turning point in his career came as a result of his travels to Europe in the early 1950s, where he studied and admired its medieval buildings and ancient ruins. Consequently, he developed his own approach to architecture, combining modernism and insights garnered from the ancient.

During his teaching career at Yale, Kahn designed the Yale Art Gallery, which won him major recognition and displayed his unique style. Kahn was interested in many fundamental aspects of architecture, which led him to use strong, simple, geometric shapes; utilize natural lighting to advantage; and weigh the importance of the “served” spaces (such as laboratories) versus the “servant” spaces (such as hallways). A major statement of these fundamentals was one of his first projects while at the University of Pennsylvania, the Richards Laboratories, which were completed in 1961.

From this point Kahn’s prominence in the architectural world only grew, both nationally and internationally. Some of Kahn’s more famous works include the Salk Institute in California (1965), the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas (1972), the Exeter Academy Library in New Hampshire (1972), and the new legislative capital in Dacca, Pakistan. His work in the Philadelphia area included dormitories at Bryn Mawr College and Mill Creek Public Housing in West Philadelphia.

In his writings and lectures, Kahn provided an original, ambitious, and philosophical perspective that influenced many architects. He called himself “a maker of spaces,” and described building materials as having needs and desires that it was his job as an architect to fulfill. Kahn was very concerned with the psychological impact of the way a building was configured.

Kahn, the least of whose work had been in the Philadelphia area, expressed surprise when he won the Philadelphia Award in 1970, stating that he would now have to “roll up his sleeves to prove that he was worthy of it.” Mary Bok, widow of award founder Edward Bok, praised Kahn for having “the courage to develop his own potential” under adverse circumstances. Like her husband, Kahn had grown up poor in America, raised by immigrant fathers who had difficulty adapting to American ways.

Kahn died in New York City in 1974, on his return trip from India where he was overseeing a project in Ahmedabad. While many of his projects were in various stages of building at the time of his death, they were all eventually finished. Although he had many plans for other structures, it is in the enduring facades of his buildings that Louis I. Kahn lives on.

1969

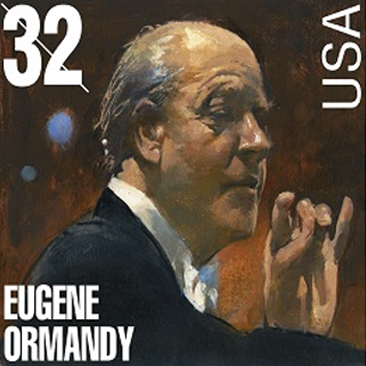

In 1921 Ormandy left Budapest for New York City, expecting to participate in a sponsored tour that never came to fruition. Stranded without money, he learned English, changed his name to Eugene Ormandy, and found a job with the Capitol Theater Symphony, the orchestra of a silent movie palace. Conductor Erno Rapee moved the violinist from last chair to concertmaster within a week. Rapee declared that Ormandy was “much too good to play in a movie house” and “should be playing in Carnegie Hall!”

Ormandy learned conducting under Rapee. When Rapee left the orchestra in 1926, Ormandy took his place as conductor. Ormandy later signed with concert manager Arthur Judson, conducting orchestras on Judson’s radio network. He regularly attended rehearsals by Arturo Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic, improving his skills as a conductor by observing the great maestro perform. When Toscanini cancelled a two-week appearance with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy jumped at the offer to conduct in his place. Substituting for one of the masters, his exemplary work earned national headlines and a job offer from the Minneapolis Symphony. A delighted Ormandy boarded the train for Minneapolis without stopping to change his concert clothes.

A guest conductor for the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy was named co-director with Leopold Stokowski in 1936 and became sole music director in 1938. Though replacing a popular conductor, Ormandy soon captivated the audience with his “Philadelphia Sound,” a sumptuous string sound created through “broad vibrato and heavy bowing.” Despite a huge repertoire, Ormandy usually conducted from memory, without a music score. Ormandy and the orchestra toured the United States, Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Their tour to China in 1973 was the first by an American orchestra.

Ormandy crafted a family atmosphere within the orchestra, perhaps a result of the absence of children in his own life. (Ormandy’s only two children died in infancy, twelve years apart, from a blood disorder.) Ormandy’s “boys and girls, my children and my family,” as Ormandy once referred to the musicians, benefited in many ways, including interest-free loans to buy rare instruments or the comforting ear of the ‘Queen Mother,’ Ormandy’s second wife, Gretel, when scolded by the maestro. Ormandy’s chosen successor, Ricardo Muti, noted that Ormandy “made the Philadelphia Orchestra into a world-famous orchestra, but he also made it into a family.”

Ormandy’s accomplishments are unrivaled. His 44 years with the Orchestra, from 1936 until 1980, represent the longest tenure of any major-orchestra conductor. His nearly 400 recordings leave a vast and treasured body of work. He premiered new works by many modern composers, including Rachmaninoff, Bartok, and Samuel Barber. Besides honors from foreign governments including Finland, Denmark and France, Ormandy received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Nixon in 1970 and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1976. Former concertmaster Norman Carol noted the preeminence of Philadelphia in foreign cities, “not for our sports teams or our industry, but [for] the Philadelphia Orchestra.” Ormandy won the 1969 Philadelphia Award for that achievement.

1968

Agraduate of South Philadelphia High School, Foster worked a variety of jobs while pursuing a college education, including shipyard worker, cabdriver, and mail carrier. He graduated from Cheyney State College, and began teaching in Philadelphia public schools in 1949, earning various promotions along the way.

In 1966 Foster became the first black principal of a Philadelphia senior high school, assigned to Simon Gratz with the task of making significant improvements at the school. Gratz was infamous for its city-highest levels of truancy and dropouts, with a graduation rate of only 72%. Only 18 of its graduating seniors from the previous year had pursued higher education. According to Mary James, community coordinator at the school, “Gratz didn’t have a band; it didn’t have [new] uniforms for its sports teams and no one could find the college guidance office before Marcus [Foster] came here.”

Making an immediate impact, Foster burned the school’s hand-me-down athletic uniforms and ordered new ones. Within three years Foster had instituted a band, a choir and an honor society, and built a new gymnasium. He sought to instill a sense of pride in the student body; student chants of “Gratz is for rats” were soon replaced with “Gratz is Great” buttons. Foster worked to bring dropouts back to school, often through personal visits. His “Go for Gratz” campaign re-enrolled 150 dropouts in one day and 225 within a week’s time. School parent Mrs. Arrie Ellis said: “My son would not have graduated if it hadn’t been for Dr. Foster.” Foster instituted a night school for career skills development and persuaded local research laboratories to train students in medicine and biochemistry. He established a nursing training program. By 1968, 180 of the graduates were heading to college, and had received $166,000 in scholarships.

In 1970, Foster became superintendent of the Oakland Unified School District, the first black man to fill that role in any large California school district. Foster took the position to determine whether his developed ideas could “be used to get a whole school system moving and a whole community involved in the schools.” Foster encountered initial resistance from the Black Caucus (a radical group) for their exclusion from the selection process and from black militants “for accusing them of creating racial tensions.” Foster said, “I stepped on some toes and did receive severe threats, but it was just so much talk. It’s more bark than bite.” Foster soon began to make progress, rewarding perfect attendance to counteract high truancy and working to bring peace to the schools.

Foster was murdered on November 6, 1973, by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a left-wing urban militant group famously known for its kidnapping of Patty Hearst, shortly after their execution of Foster. He was shot as he left work, struck seven times in the back and once in the stomach by cyanide-laced bullets. Ironically, despite all of his work for black students, the SLA viewed Foster as an enemy of black people. They killed him for his alleged support of a student identification card program and for police patrols in school buildings, but in fact he opposed both proposals. Although his life was cut tragically short, Foster’s legacy lives on through the Marcus Foster Education Fund, an organization that promotes community involvement as the best way to transform urban education.

1967

Dilworth and Clark were known as the reform mayors, and set about to end decades of corruption at the hands of the city’s Republican Party machine. He swept into office in 1956 with a 132,000-vote margin and easily won reelection. After resigning to run unsuccessfully for governor, he was appointed to the Board of Education—a nearly universally regarded thankless task. As he did with city government, Dilworth applied the concept of reform to the city schools, updating facilities and increasing teacher pay. He and his superintendent, Mark Shield, helped guide the schools though integration. The “reform” era came to a screeching halt in 1972 when Frank Rizzo became mayor. In anticipation of that day, Dilworth resigned from the school board and resumed the practice of law.

But it was his time as mayor which left a more lasting impact. During the “Reform Decade” of Clark and Dilworth, Philadelphia tore down the “Chinese wall” of elevated tracks, which bisected much of Center City. The city expanded the airport, and created a planning department, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, and the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority. Philadelphia became the first major city to fluoridate its water in, as one reporter wrote, “an era when fluoridation was thought to be a Communist plot.”

One of the most shocking things Dilworth did was move his family from the fashionable Rittenhouse Square neighborhood to the (then) unfashionable Society Hill district. He hoped that middle-class whites would follow, and they did. (So much so, that today a good number of Philadelphians think the “society” in Society Hill refers to social class, instead of William Penn’s land grant to London’s Free Society of Traders in 1683.) Dilworth was once described as “Jay Gatsby in reverse: a man who started out as a legitimate upper-class WASP, then spent his life trying to live that circumstance down…he could never take seriously the idea that wealth was a virtue and not an accident of birth.”

He was, as they say, a character. Dilworth’s time was an era where one could describe an adversary as “that mountain of lard,” as he indeed once did, and not really be any worse off, politically, for having done so. When another opponent refused to debate him, Dilworth had his own daughter put on a sandwich board, walk back and forth in front of the proposed debate site, and proclaim: “Why won’t you debate the issues with my father on TV?” On the doomed Andrea Doria, as he and his wife were preparing to head for the lifeboats, he wanted to get his socks on first. His wife replied: “For God’s sake, forget your socks so we can get off this sinking ship.”

An editorial cartoon ran shortly after Richardson Dilworth’s death. It was of an angel announcing that at the gate was “A Mister Richardson Dilworth…with a list of reforms.”

The Dilworth Family Papers are at The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

1966

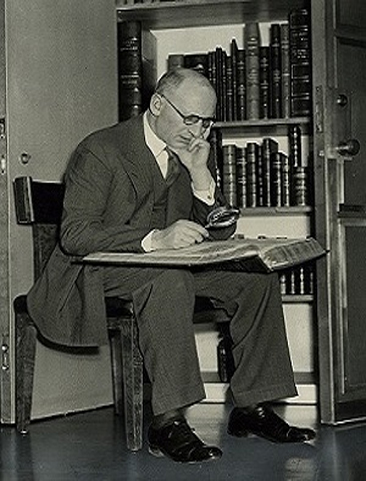

Yes, Lessing Rosenwald was no mere art hoarder; in fact, he really was not an art hoarder at all. At any given time, items from his prized collection of prints and rare books could be found at up to sixty national and international exhibits. At the time of the Award, his print collection numbered 25,000 and included works by Rembrandt, Picasso, Munch, and Matisse. His prized book collection of some 2,500 titles included the first illustrated Bible (the Giant Bible of Mainz), published in German in 1475; Epistolae et Evangelia (1495)—known as the “finest illustrated book of the fifteenth century”; and a “Baedeker-like guide book to Rome” (1488). He believed “that a work of art that is never seen is little better off than one that has never been created.” In 1943, Rosenwald announced that (upon his death), he was leaving his rare books to the Library of Congress and his prints to the National Gallery of Art.

In the meantime, his magnificent collections were available for public perusal at the Alverthorpe gallery, the fireproof wing of his mansion in Jenkintown. This perusal was by appointment only, but appointments were made steadily at first and gradually came in fast and furious, as many thousands visited the gallery. Heir to the Sears & Roebuck fortune, Rosenwald opened Alverthorpe in 1939, shortly after he retired from his position as chairman of the board of Sears and Roebuck, in order to devote himself full-time to his collections and philanthropy.

When at home, Rosenwald often greeted visitors to the gallery, shook their hands, inquired about their visit, and joked with them; he was thrilled by the great interest in his collection, not only from art connoisseurs and scholars, but from groups of adults and school children who arrived with little knowledge and left stimulated by what they had seen.

Rosenwald received the Philadelphia Award, not for amassing a great collection, but for making that collection available to the public, especially at Alverthorpe. He was also honored for his “dedicated intelligence,” which he had demonstrated by his work developing the print and drawing department of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, expanding the rare book department of the Free Library, and founding the Print Council of America.

1965

Sullivan grew up poor in West Virginia, reared by his devoutly Christian grandmother. He graduated from West Virginia State College, and earned a degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City. In 1950 Sullivan became pastor of ZionBaptistChurch in North Philadelphia. Shortly afterwards, Sullivan founded the Citizens Committee Against Juvenile Delinquency and its Causes, which organized people in low-income black neighborhoods to clean up their blocks, supervise teenagers, and protest nuisance bars.

In 1960 Sullivan and other black ministers founded 400 Ministers, to combat job discrimination. He estimated that in Philadelphia less than 1 per cent of private sector jobs involving contact with customers were held by African Americans; these jobs included clerks, bank tellers, and sales people. Few blacks held skilled factory jobs. 400 Ministers organized boycotts of Tastykake, Sun Oil Company, and five other businesses, forcing those companies to change their practices. “After the Tasty victory,” Sullivan recalled, “black people were walking ten feet tall in the streets of Philadelphia.” Numerous companies avoided boycotts by reaching agreements with the group.

In 1964 Sullivan opened the Opportunities Industrialization Center to provide vocational training for black youths. The center soon featured eight training programs, including sheet metal working, electronics assembly, and restaurant services. With corporate, foundation, and federal funding, the OIC grew into a national job training organization, operating in 150 cities by 1970.

Sullivan devised the 10-36 Plan, where parishioners would donate $10 every month for 36 months (for 16 of those months the money would go to a community nonprofit, the last 20 months to start a black-owned business). After their contributions, the parishioners were voting shareholders in the business. The largest enterprise the plan launched was Progress Plaza, a shopping complex near Temple University.

Later, he gave his name to an early driving force against the Apartheid regime in South Africa, the Sullivan Principles. These principles required international companies doing business in South Africa to ignore the race segregation laws, provide equal pay for equal work, set up training programs, and promote non-whites to supervisory positions. While companies such as Ford and GM (where Sullivan was a board member) were quick to sign on, the principles themselves had mixed success and were abandoned in 1987, when Sullivan endorsed a full economic boycott of South Africa. In 1999 Sullivan adapted the principles internationally as the Global Sullivan Principles of Corporate Social Responsibility.

In 1988 Sullivan retired as pastor of Zion Baptist, in order to devote himself to international work. He organized summits that brought together Africans and African-Americans. At the Millennium Summit in Ghana, over 3,500 attended, including the leaders of 19 African nations.

Sullivan was a tireless proponent of self-help. He inspired and assisted thousands of African-Americans in starting up businesses and learning skills to improve their economic well being. As Sullivan explained, “I long to see the kingdom of God a reality in the everyday lives of men. Some people look for milk and honey in heaven, while I look for ham and eggs on earth.”

Sullivan received honorary doctorates from over 50 institutions. President Bush awarded him the Medal of Freedom in 1992. Bill Clinton presented him with the Eleanor Roosevelt Award in 1999.